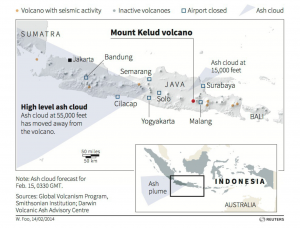

In the piece below, my friend Jon Rea shares a first-hand account of the fall-out from the deadly volcanic eruption of Mt. Kelud in Indonesia–where Javanese cities like Solo, Yogyakarta, Malang, and Surabaya have been showered with volcanic ash. Over the week-end, 100,000 people were evacuated, and several airports were closed.

From Hell, With Love

Jon Rea

February 17th 2014

Solo, Indonesia

This Valentine’s Day in New York, pure white snow was falling from heaven. On the other side of the world, however, Indonesia got a Valentine’s missive from below. Gunung Kelud committed suicide; its death wish was the spreading of its ashes as far as 600 kilometers away. Three days later, Java’s 140 million citizens, and millions more in Sumatra, are still struggling to cope with the disaster, and the ash cloud is still spreading.

It started with a big, low rumble on Thursday night that we thought was our neighbor playing his annoying dangdut music too loudly, as usual. But when other friends across the city mentioned that they had also heard the noise, we realized that it was no dangdut party. Some 200 kilometers to the east of Solo, Gunung (Mount) Kelud, one of Indonesia’s most violent and destructive volcanoes, had erupted for the first time since 2007.

Living in the most active volcano region in the world, with Gunung Merapi and Gunung Merbabu on our western horizon, and Gunung Lawu in the East on clear days, we went to bed and didn’t think much more about it. We woke up on Valentine’s Day to a bizarre snow-grey-white ash falling from the sky, blanketing the cars and roads, trees and crops and roofs beneath.

Indonesian houses are built to be open to the generally benign tropical weather, and the ash was coming straight inside through the permanently open windows. It was sticking to sheets and pillows, clothes and furniture, dishes, TVs, and this writer is still wiping it out of his computer as he types, 3 days later. The internet was down. Only one TV station seemed up-to-date on the occurring disaster, and they had naturally put their focus closer to the sight of the eruption. My wife and I didn’t know what to do.

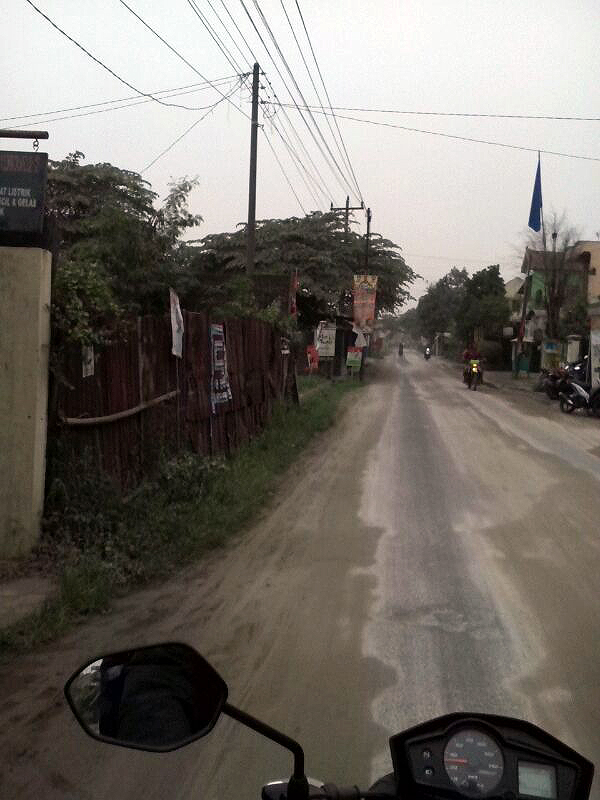

We tried to stay inside, but every second there was more and more dust coming in. We worried about our family, and decided to drive over to their house, 5 kilometers away. We put on face masks, closed our helmet visors, and drove our motorbike out through the wasteland, which looked exactly like a swirling snow flurry. It wasn’t until 2 days later, when the internet was up again, that we found out what a dangerous thing we had done.

Nobody was aware that the ash was so dangerous. The news channels said to stay inside and wear masks, but less than 12 hours after the eruption, almost every roadside store was sold out of masks, and you still had to drive to the store to look for your mask in the first place. We read about the danger of the ash, finally, on a friend’s Facebook page 2 days later. Its extra-fine size and jagged silicon structure make it extremely dangerous to inhale and damaging to the eyes.

No one had any information about what to do for the first 2 days. We never saw any police or any other government workers, we were on our own. People were outside their houses, holding their shirts over their noses, trying in vain to sweep away the ash. They were inside their houses, beating the dust off of clothes and back into the air where they could breathe it. They were riding on bicycles and motorbikes with no protection, stirring up the dust on the road. For two long, dry days, the citizens of Central Java lived and breathed the remains of Gunung Kelud.

News sources were speaking of only three victims of the eruption, but the number of deaths from breathing complications will never be counted or compiled. Personally, I know three such cases myself, from the last three days.

One victim was my friend, an expert Gamelan musician with a long history of lung problems. Another was a neighbor who passed away from a heart attack, the third a distant Aunt who died of unknown causes. No one can say how much of this could have been prevented, given the proper level of support and information.

The silver lining to this ash cloud came on Sunday, when the rain came. The wind came first, bringing more ash into the air and into the house, and into our eyes. But then the rain came, and we finally got our Valentine’s chocolate–it came cascading in waterfalls down from the roof and collected in lakes and rivers in the yards and roads, where it stuck, and as I type, still sits.

The thick mud acts like concrete, sticking to the surface of the road and the top of the soil, refusing to be washed away. It’s clogging drains now, just sitting there and waiting to get dry again.

We’re trying to shovel it up and put it out of sight, trying to sweep it out of our houses and wash it off our clothes. We’re going back to school and work on Monday. So ineffectual, but we have to try. This is a battle of nature now–let’s hope the rain wins.